If asked to describe a successful business, most people will tell you that it is one that makes money and that is not an unreasonable starting point, but it is not a good ending point. For a business to be a success, it is not just enough that it makes money but that it makes enough money to compensate the owners for the capital that they have invested in it, the risk that they are exposed to and the time that they have to wait to get their money back. That, in a nutshell, is how we define investment success in corporate finance and in this post, I would like to use that perspective to measure whether publicly traded companies are successful.

Measuring Investment Returns

Measuring Investment Returns

The first step towards measuring investment success is measuring the return that companies make on their investments. This step, though seemingly simple, is fraught with difficulties. First, corporate measures of profits are not only historical (as opposed to future expectations) but are also skewed by accounting discretion and practice and year-to-year volatility. Second, to measure the capital that a company have invested in its existing investments, you often have begin with what is shown as capital invested in a balance sheet, implicitly assuming that book value is a good proxy for capital invested. Notwithstanding these concerns, analysts often compute a return on invested capital (ROIC) as a measure of investment return earned by a company:

This simple computation has become corporate financeâs most widely computed and used ratio and while I compute it and use it in a variety of contexts, I do so with the recognition that it comes with flaws, some of which can be fatal. In the context of reporting this statistic at the start of last year, I reported my ROIC caveats in a picture:

Put simply, it would be unfair of me to tar a company like Tesla as a failure because it has a negative return on invested capital, because it is a company early in its life cycle, and dangerous for me to view HP as a company that has made good investments, because it has a high ROIC, because that is only because it has written off almost $16 billion of mistakes, reducing its invested capital and inflating its ROIC. I compute the return on invested capital at the start of 2017 for each company in my public company sample of 42,668 firms, using the following judgments in my estimation:

I do make adjustments to operating income and invested capital that reflect my view that accounting miscategorizes R&D and operating leases. I am still using a bludgeon rather than a scalpel here and the returns on invested capital for some companies will be off, either because the last yearâs operating income was abnormally high or low and/or accountants have managed to turn the invested capital at this company into a number that has little to do with what is invested in projects. That said, I have the law of large numbers as my ally.

Measuring Excess Returns

If the measure of investment success is that you are earning more on your capital invested than you could have made elsewhere, in an investment of equivalent risk, you can see why the cost of capital becomes the other half of the excess return equation. The cost of capital is measure of what investors can generate in the market on investments of equivalent risk. Thus, a company that can consistently generate returns on its invested capital that exceed its cost of capital is creating value, one that generates returns equal to the cost of capital is running in place and one that generates returns that are less than the cost of capital, it is destroying value. Of course, this comparison can done entirely on an equity basis as well, using the cost of equity as the required rate and the return on equity as a measure of return:

In general, especially when comparing large numbers of stocks across many sectors, the capital comparison is a more reliable one than the equity comparison. My end results for the capital comparison are summarized in the picture below, I break my global companies into three broad groups; the first, value creators, includes companies that earn a return on invested capital that is at least 2% greater than the cost of capital, the second, value zeros, includes companies that earn within 2% (within my estimation error) of their cost of capital in either direction and the third, value destroyers, that earn a return on invested capital that is 2% lower than the cost of capital or worse.

The public market place globally, at least at the start of 2017, has more value destroyers than value creators, at least based upon 2016 trailing returns on capital. The good news is that there are almost 6000 companies that are super value creators, earning returns on capital that earn 10% higher than the cost of capital or more. The bad news is that the value destroying group has almost 20,000 firms (about 63% of all firms) in it and a large subset of these companies are stuck in their value destructive ways, not only continuing to stay invested in bad businesses, but investing more capital.

If you are wary because the returns computed used the most recent 12 months of data, you are right be. To counter that, I also computed a ten-year average ROIC (for those companies with ten years of historical data or more) and that number compared to the cost of capital. As you would expect with the selection bias, the results are much more favorable, with almost 77% of firms earning more than their cost of capital, but even over this much longer time period, 23% of the firms earned less than the cost of capital. Finally, if you are doing this for an individual company, you can use much more finesse in your computation and use this spreadsheet to make your own adjustments to the number.

Regional and Sector Differences

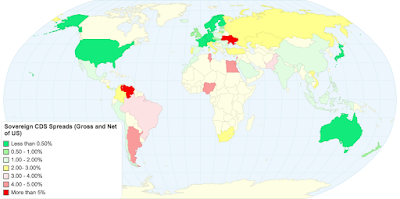

If you accept my numbers, a third of all companies are destroying value, a third are running in place and a third are creating value, but are there differences across countries? I answer that question by computing the excess returns, by country, in the picture below:

Just a note on caution on reading the numbers. Some of the countries in my sample, like Mali and Kazakhstan have very few companies listed and the numbers should taken with a grain of salt. Breaking out the excess returns by broad regional groupings, here is what I get:

Finally, I took a look at excess returns by sector, both globally and for different regions of the world, comparing returns on capital on an aggregated basis to the cost of capital. Focusing on non-financial service sectors, the sectors that delivered the most negative and most positive excess returns (ROIC - Cost of Capital) are listed below:

If you are wary because the returns computed used the most recent 12 months of data, you are right be. To counter that, I also computed a ten-year average ROIC (for those companies with ten years of historical data or more) and that number compared to the cost of capital. As you would expect with the selection bias, the results are much more favorable, with almost 77% of firms earning more than their cost of capital, but even over this much longer time period, 23% of the firms earned less than the cost of capital. Finally, if you are doing this for an individual company, you can use much more finesse in your computation and use this spreadsheet to make your own adjustments to the number.

Regional and Sector Differences

If you accept my numbers, a third of all companies are destroying value, a third are running in place and a third are creating value, but are there differences across countries? I answer that question by computing the excess returns, by country, in the picture below:

|

| Link to live map |

Just a note on caution on reading the numbers. Some of the countries in my sample, like Mali and Kazakhstan have very few companies listed and the numbers should taken with a grain of salt. Breaking out the excess returns by broad regional groupings, here is what I get:

|

| Spreadsheet with country data |

|

| Spreadsheet with sector data |

Many of the sectors that delivered the worst returns in 2016 were in the natural resource sectors, and depressed commodity prices can be fingered as the culprit. Among the best performing sectors are many with low capital intensity and service businesses, though tobacco tops the list with the highest return spread, partly because the large buybacks/dividends in the sector have shrunk the capital invested in the sector.

For investors, looking at this listing of good and bad businesses in 2017, I would offer a warning about extrapolating to investing choices. The correlation between business quality and investment returns is tenuous, at best, and here is why. To the extent that the market is pricing in investment quality into stock prices, there is a very real possibility that the companies in the worst businesses may offer the best investment opportunities, if markets have over reacted to investment performance, and the companies in the best businesses may be the ones to avoid, if the market has pushed up prices too much. There is, however, a corporate governance lesson worth heeding. Notwithstanding claims to the contrary, there are many companies where managers left to their own devices, will find ways to spend investor money badly and need to be held to account.

For investors, looking at this listing of good and bad businesses in 2017, I would offer a warning about extrapolating to investing choices. The correlation between business quality and investment returns is tenuous, at best, and here is why. To the extent that the market is pricing in investment quality into stock prices, there is a very real possibility that the companies in the worst businesses may offer the best investment opportunities, if markets have over reacted to investment performance, and the companies in the best businesses may be the ones to avoid, if the market has pushed up prices too much. There is, however, a corporate governance lesson worth heeding. Notwithstanding claims to the contrary, there are many companies where managers left to their own devices, will find ways to spend investor money badly and need to be held to account.

What next?

I am not surprised, as some might be, by the numbers above. In many companies, break even is defined as making money and profitable projects are considered to be pulling their weight, even if those profits donât measure up to alternative investments. A large number of companies, if put on the spot, will not even able to tell you how much capital they have invested in existing assets, either because the investments occurred way in the past or because of the way they are accounted for. It is not only investors who bear the cost of these poor investments but the economy overall, since more capital invested in bad businesses means less capital available for new and perhaps much better businesses, something to think about the next time you read a rant against stock buybacks or dividends.

YouTube Video

Spreadsheet

Datasets

YouTube Video

Spreadsheet

Datasets

Data 2017 Posts

- Data Update 1: The Promise and Perils of Big Data

- Data Update 2: The Resilience of US Equities

- Data Update 3: Cracking the Currency Code - January 2017

- Data Update 4: Country Risk and Pricing, January 2017

- Data Update 5: A Taxing Year Ahead?

- Data Update 6: The Cost of Capital in January 2017

- Data Update 7: Profitability, Excess Returns and Corporate Governance- January 2017

- Data Update 8: The Debt Trade off in January 2017

- Data Update 9: Dividends and Buybacks in 2017

- Data Update 10: A Pricing Update in January 2017